Long, long ago, in a certain tsardom there lived an old man and an old woman and their daughter Vasilisa. They had only a small hut for a home, but their life was a peaceful and happy one. However, even the brightest of skies may become overcast, and misfortune stepped over their threshold at last. The old woman fell gravely ill and, feeling that her end was near, she called Vasilisa to her bedside, gave her a little doll, and said: "Do as I tell you, my child. Take good care of this little doll and never show it to anyone. If ever anything bad happens to you, give the doll something to eat and ask its advice. It will help you out in all your troubles." And, giving Vasilisa a last, parting kiss, the old woman died. The old man sorrowed and grieved for a time, and then he married again. He had thought to give Vasilisa a second mother, but he gave her a cruel stepmother instead. The stepmother had two daughters of her own, two of the most spiteful, mean and hard to please young women that ever lived. The stepmother loved them dearly and was always kissing and coddling them, but she nagged at Vasilisa and never let her have a moment's peace. Vasilisa felt very unhappy, for her stepmother and stepsisters kept chiding and scolding her and making her work beyond her strength. They hoped that she would grow thin and haggard with too much work and that her face would turn dark and ugly in the wind and sun. All day long they were at her, one or the other of them, shouting: "Come, Vasilisa! Where are you, Vasilisa? Fetch the wood, don't be slow! Start a fire, mix the dough! Wash the plates, milk the cow! Scrub the floor, hurry now! Work away and don't take all day!" Vasilisa did all she was told to do, she waited on everyone and always got her chores done on time. And with every day that passed she grew more and more beautiful. Such was her beauty as could not be pictured and could not be told, but was a true wonder and joy to behold. And it was her little doll that helped Vasilisa in everything. Early in the morning Vasilisa would milk the cow and then, locking herself in in the pantry, she would give some milk to the doll and say: "Come, little doll, drink your milk, my dear, and I'll pour out all my troubles in your ear, your ear!"

And the doll would drink the milk and comfort Vasilisa and do all her work for her. Vasilisa would sit in the shade twining flowers into her braid and, before she knew it, the vegetable beds were weeded, the water brought in, the fire lighted and the cabbage watered. The doll showed her a herb to be used against sun-burn, and Vasilisa used it and became more beautiful than ever. One day, late in the fall, the old man set out from home and was not expected back for some time. The stepmother and the three sisters were left alone. They sat in the hut and it was dark outside and raining and the wind was howling. The hut stood at the edge of a dense forest and in the forest there lived Baba-Yaga, a cunning witch and sly, who gobbled people up in the wink of an eye. Now to each of the three sisters the stepmother gave some work to do: the first she set to weaving lace, the second to knitting stockings, and Vasilisa to spinning yarn. Then, putting out all the lights in the house except for a single splinter of birch that burnt in the corner where the three sisters were working, she went to bed. The splinter crackled and snapped for a time, and then went out. "What are we to do?" cried the stepmother's two daughters. "It is dark in the hut, and we must work. One of us will have to go to Baba-Yaga's house to ask for a light." "I'm not going," said the elder of the two. "I am making lace, and my needle is bright enough for me to see by." "I'm not going, either," said the second. "I am knitting stockings, and my two needles are bright enough for me to see by." Then, both of them shouting: "Vasilisa is the one, she must go for the light! Go to Baba-Yaga's house this minute, Vasilisa!" they pushed Vasilisa out of the hut. The blackness of night was about her, and the dense forest, and the wild wind. Vasilisa was frightened, she burst into tears and she took out her little doll from her pocket. "O my dear little doll," she said between sobs, "they are sending me to Baba-Yaga's house for a light, and Baba-Yaga gobbles people up, bones and all." "Never you mind," the doll replied, "you'll be all right. Nothing bad can happen to you while I'm with you." "Thank you for comforting me, little doll," said Vasilisa, and she set off on her way. About her the forest rose like a wall and, in the sky above, there was no sign of the bright crescent moon and not a star shone.

Vasilisa walked along trembling and holding the little doll close.

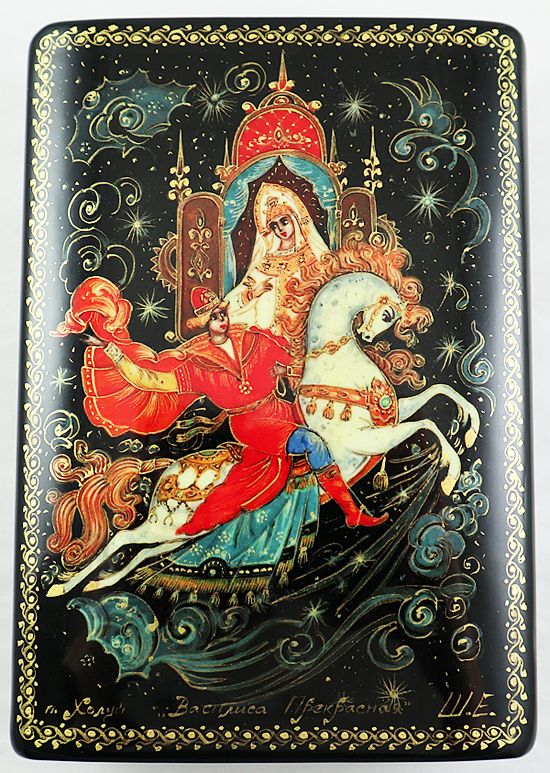

All of a sudden whom should she see but a man on horseback galloping past. He was clad all in white, his horse was white and the horse's harness was of silver and gleamed white in the darkness. It was dawning now, and Vasilisa trudged on, stumbling and stubbing her toes against tree roots and stumps. Drops of dew glistened on her long plait of hair and her hands were cold and numb. Suddenly another horseman came galloping by. He was dressed in red, his horse was red and the horse's harness was red too. The sun rose, it kissed Vasilisa and warmed her and dried the dew on her hair. Vasilisa never stopped but walked on for a whole day, and it was getting on toward evening when she came out on to a small glade. She looked, and she saw a hut standing there. The fence round the hut was made of human bones and crowned with human skulls. The gate was no gate but the bones of men's legs, the bolts were no bolts but the bones of men's arms, and the lock was no lock but a set of sharp teeth. Vasilisa was horrified and stood stock-still. Suddenly a horseman came riding up. He was dressed in black, his horse was black and the horse's harness was black too. The horseman galloped up to the gate and vanished as if into thin air. Night descended, and lo! The eyes of the skulls crowning the fence began to glow, and it became as light as if it was day. Vasilisa shook with fear. She could not move her feet which seemed to have frozen to the spot and refused to carry her away from this terrible place. All of a sudden, she felt the earth trembling and rocking beneath her, and there was Baba-Yaga flying up in a mortar, swinging her pestle like a whip and sweeping the tracks away with a broom. She flew up to the gate and, sniffing the air, cried: "I smell Russian flesh! Who is here?" Vasilisa came up to Baba-Yaga, bowed low to her and said very humbly: "It is I, Vasilisa, Grandma. My stepsisters sent me to you to ask for a light." "Oh, it's you, is it?" Baba-Yaga replied. "Your stepmother is a kinswoman of mine. Very well, then, stay with me for a while and work, and then we'll see what is to be seen." And she shouted at the top of her voice: "Come unlocked, my bolts so strong! Open up, my gate so wide!" The gate swung open, Baba-Yaga rode in in her mortar and Vasilisa walked in behind her.

Now at the gate there grew a birch-tree and it made as if to lash Vasilisa with its branches. "Do not touch the" maid, birch-tree, it was I who brought her," said Baba-Yaga. They came to the house, and at the door there lay a dog and it made as if to bite Vasilisa. "Do not touch the maid, it was I who brought her," said Baba-Yaga. They came inside and in the passage an old grumbler-nimbler of a cat met them and made as if to scratch Vasilisa. "Do not touch the maid, you old grumbler-rumbler of a cat, it was I who brought her," said Baba-Yaga. "You see, Vasilisa," she added, turning to her, "it is not easy to run away from me. My cat will scratch you, my dog will bite you, my birch-tree will lash you, and put out your eyes, and my gate will not open to let you out." Baba-Yaga came into her room, and she stretched out on a bench. "Come, black-browed maid, give us something to eat," she cried. And the black-browed maid ran in and began to feed Baba-Yaga. She brought her a pot of borshch and half a cow, ten jugs of milk and a roasted sow, twenty chickens and forty geese, two whole pies and an extra piece, cider and mead and home-brewed ale, beer by the barrel and kvass by the pail. Baba-Yaga ate and drank up everything, but she only gave Vasilisa a chunk of bread. "And now, Vasilisa," said she, "take this sack of millet and pick it over seed by seed. And mind that you take out all the black bits, for if you don't I shall eat you up." And Baba-Yaga closed her eyes and began to snore. Vasilisa took the piece of bread, put it before her little doll and said: "Come, little doll, eat this bread, my dear, and I'll pour out all my troubles in your ear, your ear! Baba-Yaga has given me a hard task to do, and she threatens to eat me up if I do not do it." Said the doll in reply: "Do not grieve and do not weep, but close your eyes and go to sleep. For morning is wiser than evening." And the moment Vasilisa was asleep, the doll called out in a loud voice:

“Tomtits, pigeons, sparrows, hear me,

There is work to do, I fear me.

On your help, my feathered friends,

Vasilisa's life depends.

Come in answer to my call,

You are needed, one and all”.

And the birds came flying from all sides, flocks and flocks of them, more than eye could see or tongue could tell. They began to chirp and to coo, to set up a great to-do, and to pick over the millet seed by seed very quickly indeed. Into the sack the good seeds went, and the black went into the crop, and before they knew it the night was spent, and the sack was filled to the top. They had only just finished when the white horseman galloped past the gate on his white horse. Day was dawning. Baba-Yaga woke up and asked: "Have you done what I told you to do, Vasilisa?" "Yes, it's all done, Grandma." Baba-Yaga was very angry, but there was nothing more to be said. "Humph," she snorted, "I am off to hunt and you take that sack yonder, it's filled with peas and poppy seeds, pick out the peas from the seeds and put them in two separate heaps. And mind, now, if you do not do it, I shall eat you up." Baba-Yaga went out into the yard and whistled, and the mortar and pestle swept up to her. The red horseman galloped past, and the sun rose. Baba-Yaga got into the mortar and rode out of the yard, swinging her pestle like a whip and whisking the tracks away with a broom. Vasilisa took a crust of bread, fed her little doll and said: "Do take pity on me, little doll, my dear, and help me out." And the doll called out in ringing tones: "Come to me, î mice of the house, the barn and the field, for there is work to be done!" And the mice came running, swarms and swarms of them, more than eye could see or tongue could tell, and before the hour was up the work was all done. It was getting on toward evening, and the black-browed maid set the table and began to wait for Baba-Yaga's return.The black horseman galloped past the gate, night fell, and the eyes of the skulls crowning the fence began to glow. And now the trees groaned and crackled, the leaves rustled, and Baba-Yaga, the cunning witch and sly, who gobbled people up in the wink of an eye, came riding home. "Have you done what I told you to do, Vasilisa?" she asked. "Yes, it's all done, Grandma."

Baba-Yaga was very angry, but what could she say! "Well, then, go to bed. I am going to turn in myself in a minute." Vasilisa went behind the stove, and she heard Baba-Yaga say: "Light the stove, black-browed maid, and make the fire hot. When I wake up, I shall roast Vasilisa." And Baba-Yaga lay down on a bench, placed her chin on a shelf, covered herself with her foot and began to snore so loudly that the whole forest trembled and shook. Vasilisa burst into tears and, taking out her doll, put a crust of bread before it. "Come, little doll, have some bread, my dear, and I'll pour out all my troubles in your ear, your ear. For Baba-Yaga wants to roast me and to eat me up," said she. And the doll told her what she must do to get out of trouble without more ado. Vasilisa rushed to the black-browed maid and bowed low to her. "Please, black-browed maid, help me!" she cried. "When you are lighting the stove, pour water over the wood so it does not burn the way it should. Here is my silken kerchief for you to reward you for your trouble." Said the black-browed maid in reply: "Very well, my dear, I shall help you. I shall take a long time heating the stove, and I shall tickle Baba-Yaga's heels and scratch them too so she may sleep very soundly the whole night through. And you run away, Vasilisa!" "But won't the three horsemen catch me and bring me back?" "Oh, no," replied the black-browed maid. "The white horseman is the bright day, the red horseman is the golden sun, and the black horseman is the black night, and they will not touch you." Vasilisa ran out into the passage, and Grumbler-Rumbler the Cat rushed at her and was about to scratch her. But she threw him a pie, and he did not touch her. Vasilisa ran down from the porch, and the dog darted out and was about to bite her. But she threw him a piece of bread, and the dog let her go. Vasilisa started running out of the yard, and the birch-tree tried to lash her and to put out her eyes. But she tied it with a ribbon, and the birch-tree let her pass. The gate was about to shut before her, but Vasilisa greased its hinges, and it swung open. Vasilisa ran into the dark forest, and just then the black horseman galloped by and it became pitch black all around. How was she to go back home without a light? What would she say? Why, her stepmother would do her to death. So she asked her little doll to help her and did what the doll told her to do. She took one of the skulls from the fence and, mounting it on a stick, set off across the forest. Its eyes glowed, and by their light the dark night was as bright as day. As for Baba-Yaga, she woke up and stretched and, seeing that Vasilisa was gone, rushed out into the passage. "Did you scratch Vasilisa as she ran past, Grumbler-Rumbler?" she demanded. And the cat replied: "No, I let her pass, for she gave me a pie. I served you for ten years, Baba-Yaga, but you never gave me so much as a crust of bread." Baba-Yaga rushed out into the yard. "Did you bite Vasilisa, my faithful dog?" she demanded. Said the dog in reply: "No, I let her pass, for she gave me some bread. I served you forever so many years, but you never gave me so much as a bone." "Birch-tree, birch-tree!" Baba-Yaga roared. "Did you put out Vasilisa's eyes for her?" Said the birch-tree in reply: "No, I let her pass, for she bound my branches with a ribbon. I have been growing here for ten years, and you never even tied them with a string." Baba-Yaga ran to the gate. "Gate, gate!" she cried. "Did you shut before her that Vasilisa might not pass?" Said the gate in reply: "No, I let her pass, for she greased my hinges. I served you forever so long, but you never even put water on them." Baba-Yaga flew into a temper. She began to beat the dog and thrash the cat, to break down the gate and to chop down the birch-tree, and she was so tired by then that she forgot all about Vasilisa. Vasilisa ran home, and she saw that there was no light on in the house. Her stepsisters rushed out and began to chide and scold her. "What took you so long fetching the light?" they demanded. "We cannot seem to keep one on in the house at all. We have tried to strike a light again and again but to no avail, and the one we got from the neighbours went out the moment it was brought in. Perhaps yours will keep burning."

They brought the skull into the hut, and its eyes fixed themselves on the stepmother and her two daughters and burnt them like fire. The stepmother and her daughters tried to hide but, run where they would, the eyes followed them and never let them out of their sight. By morning they were burnt to a cinder, all three, and only Vasilisa remained unharmed. She buried the skull outside the hut, and a bush of red roses grew up on the spot. After that, not liking to stay in the hut any longer, Vasilisa went into the town and made her home in the house of an old woman. One day she said to the old woman: "I am bored sitting around doing nothing, Grandma. Buy me some flax, the best you can find." The old woman bought her some flax, and Vasilisa set to spinning yarn. She worked quickly and well, the spinning-wheel humming and the golden thread coming out as even and thin as a hair. She began to weave cloth, and it turned out so fine that it could be passed through the eye of a needle, like a thread. She bleached the cloth, and it came out whiter than snow. "Here, Grandma," said she, "go and sell the cloth and take the money for yourself." The old woman looked at the cloth and gasped. "No, my child, such cloth is only fit for a Tsarevich to wear. I had better take it to the palace." She took the cloth to the palace, and when the Tsarevich saw it, he was filled with wonder. "How much do you want for it?" he asked. "This cloth is too fine to be sold, I have brought it to you for a present." The Tsarevich thanked the old woman, showered her with gifts and sent her home. But he could not find anyone to make him a shirt out of the cloth, for the workmanship had to be as fine as the fabric. So he sent for the old woman again and said: "You wove this fine cloth, so you must know how to make a shirt out of it." "It was not I that spun the yarn or wove the cloth, Tsarevich, but a maid named Vasilisa." "Well, then, let her make me a shirt." The old woman went home, and she told Vasilisa all about it. Vasilisa made two shirts, embroidered them with silken threads, studded them with large, round pearls and, giving them to the old woman to take to the palace, sat down at the window with a piece of embroidery. By and by whom should she see but one of the Tsar's servants come running toward her. "The Tsarevich bids you come to the palace," said the servant. Vasilisa went to the palace and, seeing her, the Tsarevich was smitten with her beauty. "I cannot bear to let you go away again, you shall be my wife," said he. He took both her milk-white hands in his and he placed her in the seat beside his own. And so Vasilisa and the Tsarevich were married, and, when Vasilisa's father returned soon afterwards, he made his home in the palace with them. Vasilisa took the old woman to live with her too, and, as for her little doll, she always carried it about with her in her pocket. And thus are they living to this very day, waiting for us to come for a stay.